Linen: a precious, zero-waste and sustainable vegetal fiber

Discover how linen is made, it's all-round sustainability, and all of its pros and cons

Linen is one of the oldest textiles known to mankind and it has always been synonymous of high-end fashion

Linen fabrics are made from the cellulose fibers that grows inside of the flax plant’s stalks, or Linum usitatissimum, one of the oldest cultivated plant fibers in human history, with findings dating back to 36,000 BC. Europe is the cradle of flax cultivation, thanks to a temperate oceanic climate and a rich soil; in fact, 80% of the world’s production still takes place in European countries – mostly France, Belgium and Netherlands – on around 100,000 hectares (approx. 247,000 acres) of land. Flax is a rare product which represents less than 1% of all textile fibers consumed worldwide, yet it has a unique role in the agro-industial industry, as 10 000 companies in 14 European Union countries are involved in the linen industry, not to mention the rest of the world. Flax is an annual plant, which means it only lives for one growing season, and it grows really quick, from seed-planting, it is ready to be harvested in about a hundred days. It grows to about three or four feet tall, with glossy bluish-green leaves and pale blue flowers, though on rare occasions, the flowers also bloom red. All without demanding a lot, just a maritime climate with its steady alternation of sun and rain paired with plenty of wind, with deep, loamy soil. Flax is cultivated around the world not only for its fine, strong fibers, but also for its seeds, which are rich in nutrients such as dietary fiber and omega-3 fatty acids. All of this makes Linen a zero-waste material, as nothing of it goes to waste. It is a material that has made its way through ages, so let’s see all of the reasons why.

How are linen fabrics made? Here's their complex and zero-waste manufacturing process

1) Cultivation & Harvesting

It takes about 100 days from seed planting to harvesting of the flax plant. Since flax plants do not tolerate heat, they must be planted in the cooler part of the year to avoid crop death. When, after approximately 90 days, leaves wither, stems turn yellow and seeds turn brown, it means it is time to harvest the plant. The plant must be pulled as soon as it appears brown as any delay results in linen without the prized luster. It is imperative that the stalk not be cut in the harvesting process but removed from the ground intact.

2) Retting

Retting is the process by which flax fibers are released from the stem of the plant by monitored natural degradation. The stalk of the plant holds together the individual flax fibers with binding compounds known as pectins. The goal of retting is then to remove these binders without harming the flax fibers. Luckily, pectins can be broken down by many of the world’s naturally occurring microorganisms, which – over the course of the retting process – consume the pectin material, and as a side effect, release the individual flax fibers from the bonds that hold them together. Equal retting on both sides of the flax is the ultimate goal, this is why the farmer has to decide when to turn the flax – another phase in which his expertise is vital. The status of the decomposing flax plants is carefully monitored and once it is determined to be of sufficient degradation, the retted flax is collected for the next phases.

*An in-depth look at "RETTING", as it can be done in different ways:

Nr. 1

Dew Retting

After the flax has been pulled, it is spread evenly in the field, and over the course of the next 3-7 weeks - depending on climatic conditions - natural decomposing bacteria dissolve the pectin material around the plant stalks. It is a fully natural process, chemical free, no labor is involved, it's inexpensive, there's no environmental damage, yields more fiber, and creates greater natural antibacterial properties on the fiber. On the other hand, there's more room for error, it can produce inconsistent and poorer quality fibers if done improperly, it takes longer than other retting methods, it requires the use of the field for the duration of the process. This form of retting relies on the expertise of farmers to know when to begin, continue, or end the process – with much on the line, as over/under-retted fibers are of low quality for textile use. Dew-retted fibers are generally darker in color and more veritable in quality than others.

Nr. 2

Water Retting

In water retting, the pulled flax plants are immediately collected from the field and submerged in a body of water; the bacteria present in the water then degrades the pectin and releases the fibers. Historically, water retting was performed in natural waters, such as bogs, ponds, lakes, dams, ditches or slow-moving streams and rivers. Nowadays, it is conducted in modern retting tanks. This process must be monitored at least on a day-to-day basis to achieve the optimal fiber quality. Generally, water retting produces a more consistent fiber than dew retting because conditions remain constant throughout the process. On the downside, water retting creates biological pollution, and therefore its wastewater must be treated prior to its release. On the one hand, it is a faster process, it can be performed in any season, results in a more consistent, finer, and stronger fiber. On the other hand, it can cause waterway pollution, wastewater requires treatment, there are little to no antibacterial properties in final fibers, it is water and labor intensive.

Nr. 3

Chemical Retting

Chemical retting is an increasingly frequent, modified version of water retting that involves immersing the plants in a chemical solution to increase the speed of fiber release – taking only a few hours. On the one hand, it is the fastest form of retting, it can be performed year-round. On the other hand, it's expensive, it gives a low quality fiber, there's a significant wastewater treatment required, it's energy and water intensive, close control is necessary.

3) Scutching

In the scutching process, the fiber is extracted by breaking the woody stalks of the plant into pieces called “shives”, all without harming the flax fiber. This used to be a labor-intensive process done by hand. Today, everything is done with “scutchers”, machines that break the stalk and separate the shives mechanically. First, flax is rolled out and spread across the conveyor belt, then the machine pulls it through large rollers, which break the stalk into shives while preserving the fiber. Then flax reaches the drums. Here, large rotating blades beat the remaining shives from the fiber, also removing shorter fibers (scutching tow). Eventually, a scutcher checks the long fibers for quality, removing everything that doesn’t meet the quality standards.

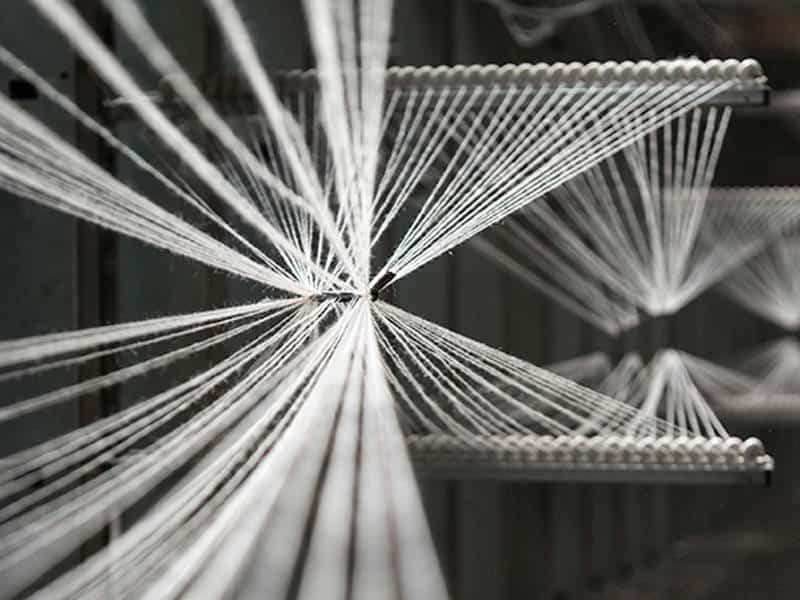

4) Hackling

The “Hackling” step removes the remaining shives and sorts out shorter fibers again. It is a mechanized combing process where thousands of pins comb the flax until only the purest fiber remains. After this, two new materials coming out of the machine are distinguished: hackle tows and flax line. The former serves as raw material for coarser yarns, whereas the latter forms the base material for the finest linen yarns. The heckled flax is composed not of individual fibres but of fibre bundles, the individual fibres of which are held together with plant-based glue.

5) SPINNING, depending on the length of the plant when harvested, one of the following techniques is suitable for further spinning:

Nr. 1

WET SPINNING for longer fibers

Fine linen thread needs to be spun wet. This process serves to obtain top quality flax yarn, often used in the clothing and household linen sector. In this process, the flax sliver is soaked in water of approximately 70°C in order to make it more flexible and thus enable the production of finer yarns.

Nr. 2

DRY SPINNING for shorter fibers

Coarse thread from tow can be spun dry. In this case, the linen yarns turn out thicker, with more of a rustic feel to them. This process consists in spinning the linen ribbons without first soaking them in water. These yarns will be used for decorative fabrics or for technical purposes.

*During all these production phases, NO PART OF THE FLAX PLANT GOES TO WASTE, this is why linen production is considered as zero-waste

Nr. 1

"LINSEED"

The seeds of the flax plant have always been harvested to guarantee successful sowing the following year. Linseed is also edible and it can be pressed to make oil. Linseeds obtained after dew retting are often damaged, and can usually only be made into oil. Higher-quality flaxseed is typically harvested at an earlier time.

Nr. 2

"SHIVES"

Shives are woody fragments that break off from inside flax plant stems during the scutching phase. Shives are used as a basic material in lightweight building boards, as an aggregate in potting soil and, first and foremost, very successfully as animal bedding.

Nr. 3

"TOW"

One by-product of this process is tow – short, coarse pieces of fibre produced during the heckling phase. Tow accounts for about 7-15% of flax straw. Higher-quality tow is used in the textile sector: it can be used as raw material for classic linen spinning mills, or shortened and refined tow can be used in staple fibre spinning mills. Medium-quality tow is used to make non-woven fibres; in the production of moulded parts or as natural insulating materials, for example. The lowest grades are used in the production of high-quality cellulose, which is necessary for special types of papers or filters.

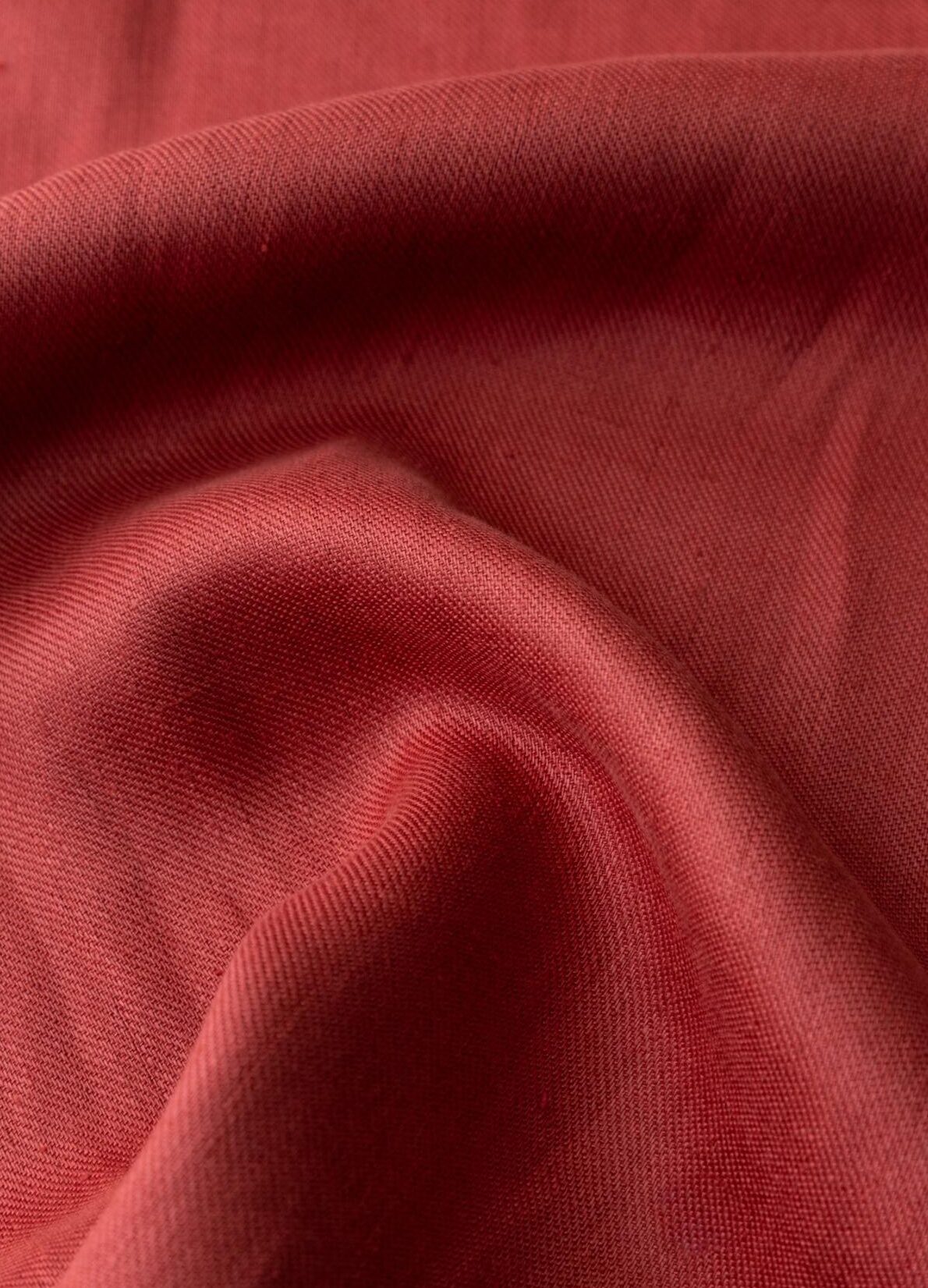

6) Textile making: coning, warping, weaving and finishing

After all these artisanal and complex cultivation and production phases, linen yarns can finally become fabrics. Linen yarn is generally woven into sheets – a process wherein multiple threads are interlaced both horizontally and vertically on a loom. Occasionally, linen yarn is also knit, or formed into fabric by creating consecutive rows of loops that intertwine with one another. By virtue of these loops, knit fabrics have a degree of stretch inherent in them, and because linen yarn has no elasticity, it is quite difficult to knit and so more frequently woven. After the greige linen fabric is done, it is send to the finishing mill, where it undergoes the dyeing process (unless it is kept with its “raw colors”)* and other physical processes to make it better.

*It naturally ranges across a neutral palette. The growing conditions of the flax plant can actually have a massive impact on the final result, which is why—as well as the famous ‘linen grey’—you can find linen fabric in ivory, tan, taupe, and ecru, too.

Let's see all the PROS & CONS of Linen

Nr. 1

Environment-friendly

Linen is made from Flax, which is environmentally friendly to grow, as it requires little irrigation and little energy to process. Furthermore, there’s hardly any pesticides needed as long as it is part of a crop rotation to protect the soil.

Nr. 2

Anti-bacterial

The flax has unique bactericidal properties, stops the development of bacteria that cause an unpleasant odor of sweat on the skin, minimizes the risk of skin diseases caused by increased sweating.

Nr. 3

Moisture regulating

Flax fibers are known for their great ability to absorb water. This is due to a high amount of pectins, the components that hold the fibers together. Pectins in linen textiles give them a «lively», heat-regulating quality. Depending on the weather, they can retain water or repel it – up to 20%* of their weight – without feeling damp to the touch. Consider that the heat dissipation performance of linen is 5 times that of wool and 19 times that of silk, in hot weather, wearing linen clothing can make the skin surface temperature 3-4 degrees Celsius lower than wearing silk and cotton clothing.

Nr. 4

Extremely durable

A structure unique to xylem fibers (those contained in the plant stem, not the flower) makes linen textiles supple and resistant without pilling or becoming distorted. Linen is one of the most robust natural fibers used in clothing textiles worldwide- ranked second to silk and evidently 30% stronger than cotton.

Nr. 5

Versatile

Linen is ideal for all uses and easily associated with other fibers, linen can be used in all densities from ultra-light, transparent batiste to the heaviest canvases. It is at the heart of textile innovations thanks to skilled European spinners and weavers who modernize its hands, finishings, coatings and textures to keep abreast of trends running from casual to sophisticated.

Nr. 6

Biodegradable

When untreated with dyes and chemicals, linen is one of the most biodegradable fabrics in the world.

Nr. 7

... Linen CREASES A LOT, but it's up to you to consider it a CONS or not

Linen fibers can vary – for example, depending on production or the addition of other fabrics. Thus, there are thicker and thinner flax fibers, which obviously affect fleshiness, bulkiness, degree of air permeability, etc. Thus, yarns made of coarse fibers are bulkier and have a more pronounced texture. Fine fibers on the other hand are more delicate, airy, soft and subtle. The latter tend to crease more – mainly due to their delicacy and uniqueness, which has been identified with nobility for years. There is a saying in Polish tradition “Linen creases but it creases in an expensive way“. These words emphasize the uniqueness of linen fabrics – by creasing, we can judge whether a person is wearing an expensive, unique fabric.

At Manteco we have long believed in Linen and all of its properties. This is why, nowadays, there's always room for it in our collections and we also obtained the European Flax® certification.

About Manteco, Italian premium textiles and circularity since 1943After decades in the fashion world, in 2018, we have created the Manteco Academy project, through which we give webinars, in-person lessons and workshops on eco-design, circular economy and sustainability to numerous fashion schools, technical universities and brands worldwide. Thanks to this educative commitment and our heritage, we are often invited as guest speaker at events, panels, podcasts and conferences about sustainable fashion and circular economy.